As economies around the world continue to reopen, investors and commentators are growing increasingly optimistic for the future. Inflows into global equities have accelerated significantly and volatility has returned as markets grapple with the outlook for inflation and interest rates. As central banks start to move towards tighter monetary policy, asset allocation looks more challenging. In a world where asset prices have enjoyed very low or negative real rates for over a decade, the search for balance and protection from a reversal of this trend yields few options. In this piece, we will examine the following areas relevant to our thinking on portfolio evolution:

1. Current outlook for inflation

2. Use of Alternative assets in portfolio construction

3. Geographic case study: Japan

As ever, we advise clients to maintain long-term perspectives on their investments as we anticipate continued short-term volatility as economic fundamentals continue to evolve.

1. Current outlook for inflation

As discussed in our March 2021 Outlook, central banks and governments have responded to the Covid-19 crisis with unprecedented levels of monetary and fiscal support. With interest rates already low relative to history before the crisis, it remains unclear how economies and markets will emerge from this fresh round of stimulus. We have already seen significant asset price inflation in bond and equity markets over the last cycle, with valuations supported by record low interest rates. We now believe that there is a reasonable possibility that inflation will move across to the real economy, driven primarily by fiscal stimulus not delivered after the Global Financial Crisis (‘GFC’). 2020 saw public debt levels expand rapidly, far exceeding the fiscal response to the GFC. With developed and developing markets all facing the same policy challenge in responding to burgeoning public debt, we believe that tolerance of a systemically higher level of inflation in the medium term is likely. Policymakers must balance the risk of rising inflationary pressure with a desire to find the most politically palatable way to ease debt levels. Given the global nature of this shock, small rises in inflation are unlikely to have detrimental effects on currencies, provided that central banks continue to act in a relatively coordinated manner.

Figure 1: Change in Global public debt levels – Global Financial Crisis vs Coronavirus Crisis. Source: Makin & Layton (2021)

The stimulus response to the GFC did not elicit significant inflation in the real economy. This has led to confidence and perhaps complacency from many commentators around the ‘transitory’ nature of potential future inflation following central bank and government response to the Covid-19 crisis. We see three key differences between the environment today compared to the environment in 2009-10.

Firstly, governments followed the GFC response with an era of austerity. Budget cuts were widespread as Treasury departments made efforts to balance their books. There was a general political consensus within the parties in power, certainly in the UK and Europe, that the money used to rescue financial institutions (and the economy more widely) would need to be ‘paid back’ in future. Today’s policy mood feels very different, perhaps because we are united against a common enemy in the form of a virus, rather than responding to perceived mismanagement of financial institutions. There has been little to no mention of austerity in the developed or developing world; even the withdrawal of stimulus has been gradual and gentle. Where we saw fiscal policy counterbalancing monetary policy in the years following the GFC, we believe that both elements will remain more accommodative this time round. This sets up a potentially much more inflationary environment for policymakers to grapple with.

Secondly, after the GFC there was a significant liquidity squeeze. We consider the case of the UK as an example, but the same trends were seen in other developed markets. Money pumped out of the Bank of England in the form of Quantitative Easing (‘QE’) did not feed through fully to the real economy. Banks, fresh from the financial crisis, built up liquidity reserves and de-risked lending procedures. Whilst this was a rational response in the context of the issues faced by the sector, it also served to keep inflationary pressure in check. Lending to businesses and households has still not recovered to the levels seen pre-GFC. The Bank of England was wise to this possibility in 2020 and monitored bank lending activity carefully to ensure liquidity did not dry up. This, in combination with Treasury lending schemes enacted by banking institutions, led to a much better environment for businesses and households following this crisis. Undoubtedly, this will have ensured the short-term survival of many businesses that would otherwise have failed and assisted many households struggling with short-term pressures. However, it also implies that stimulus has effectively flowed through the financial system and reached end users in the form of businesses and households which is likely to be inflationary.

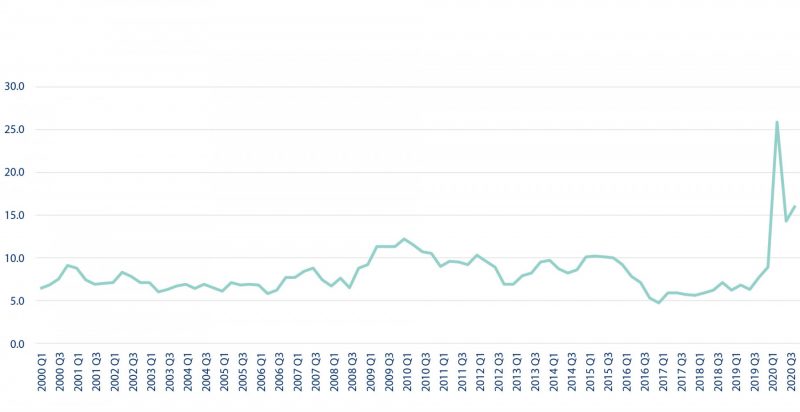

Quarterly 12-month Growth in Net Lending to Corporations and Households (%)

What businesses and households choose to do with this liquidity will have a critical role in determining the levels of inflation faced going forward. One measure we can use to monitor this is the Household Savings Rate, provided by the ONS. In 2008-9, we saw a modest rise in the level of household savings, but this relatively quickly returned to normal levels. In contrast, 2020 saw a huge spike in the level of household savings, well beyond levels seen over the last 20 years. This level did drop, but remains significantly elevated. The Covid-19 crisis has been a much more visible and impactful crisis for most people than the GFC. National lockdowns, a move to remote working and uncertainty around future job prospects have impacted behaviour to a much greater degree than anything seen during the GFC. The saving versus spending dynamic of households will go a great way towards determining inflationary pressure, certainly in the short-term. In our view, as uncertainty eases, we are likely to see households spending their newly acquired reserves. Home improvements, holidays and outings which were unavailable during the crisis, alongside a renewed sense of ‘life is short’ may prove too great a temptation for many when faced with a choice between spend and save.

Household Savings Rate (%)

We believe that inflation is likely to continue to rise from current levels and that the pressure may prove more enduring than the current rhetoric from central banks suggests. We also believe that policymakers are likely to accept systemically higher levels of inflation in the medium term in an effort to erode debt levels in a politically palatable manner. Although neither of these views predicates a steep rise in interest rates, we expect renewed volatility in equity and bond markets as investors struggle with an evolving economic environment.

2. Use of Alternative assets in portfolio construction

Alternative asset classes such as Private Equity, Hedge Funds, Commodities, Property, and Infrastructure have the potential to play an important role in improving the risk-adjusted performance of multi-asset portfolios. This can be achieved as a result of relatively lower, or even negative, correlation with bond and equity investments. With equity markets trading at historically high levels and government bond yields low, investors have increasingly focused their efforts toward identifying attractive alternative investment options. Within the Cantab portfolios, real asset exposure in the form of infrastructure and property is of particular interest.

Infrastructure as an asset class captures a vast array of investable real assets, each behaving differently through economic cycles. Examples of assets falling within this asset class include wind farms, utility infrastructure, logistics, toll roads, data centres, private hospitals, schools, and local authority housing. The diverse nature of infrastructure assets makes the use of specialist investment managers with experience in analysing individual projects desirable. In our view, there are several specific characteristics which make infrastructure assets particularly attractive:

- Predictable and often index-linked long-term cashflows provide bond-like characteristics without the associated market dynamics of a bond investment

- High barriers to market entry, offering a stable yield and relative security (often with government backed contractual arrangements) during periods of market stress

- Accessibility and liquidity of the asset class via collective investment schemes, with attractive long-term structural tailwinds in the

form of climate change policy

Many of these characteristics also apply to real estate assets. A key consideration for inclusion of both real estate and infrastructure assets in client portfolios is liquidity. The liquidity mismatch between underlying property assets and daily-dealing funds has been clear to us since the closure of direct property funds following the Brexit referendum in 2016. However, adding exposure via collective investment schemes makes a liquidity trap less likely if most of the exposure is gained via Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs), especially if most of the underlying holdings in the REIT are property shares. This mirrors the Investment Trust structure typically used for infrastructure investments.

We believe that property and infrastructure assets both play a valuable role in providing diversification benefits and attractive risk adjusted returns through the cycle in client portfolios. Exposure to real assets is appealing in times of economic uncertainty, particularly when inflationary pressure is high or rising.

3. Geographic case study: Japan

With so many significant domestic developments over the last 18 months, it is easy to neglect opportunities around the world. Cantab models have had meaningful exposure to Japanese equities since inception; this has delivered good returns for clients despite Japan’s low-inflation and low-growth economic environment. Currency is a particularly important element of the investment case for Japan. Here, we revisit this case and introduce some significant changes occurring in this market, which we view to be positive for

shareholders going forward.

The yen has long been viewed as a safe haven for investors in times of market turmoil. With Japan being one of the world’s top creditor nations through its purchases of government bonds, when there is a sell-off in bond markets, the proceeds are converted back into yen, strengthening the currency. A secondary factor which is supportive of the yen in volatile market conditions has been Japan’s aggressive monetary policy over the past few decades which has enabled investors to engage in “carry trades”. This is where the investor borrows in Japan, taking advantage of a low-interest, low-inflation environment, and lends or invests in countries where returns are higher. During a market sell-off, a portion of these carry trades are unwound, with money flowing back to Japan, strengthening the yen.

This relationship was evident when COVID-19 first hit markets, with the yen appreciating 13.0% against sterling in the four weeks to 18 March 2020. Maintaining an unhedged exposure to Japanese equities within our portfolios served to provide a natural degree of downside protection. The yen has since depreciated by >15% against sterling (to July 2021), as investors forayed back into markets, encouraged by the ultra-loose fiscal and monetary policies adopted by central banks globally. Positive momentum following a Brexit deal also led to sterling appreciating against the yen.

Beyond currency, Japan’s response to the pandemic was viewed as exemplary, with incisive government action leading to relatively low case and death numbers. This served to dampen the economic downturn in 2020, with GDP shrinking 4.8%, comparing favourably to both the eurozone (6.1%) and the UK (9.9%). One of the tailwinds to Japan’s economy in 2021 has been exports which have supported the manufacturing sector. Japan’s service sector remains in contractionary territory, with consumption remaining subdued. This is due to the vaccine approval process, which requires more clinical trials than many other countries, delaying the start for programmes. With vaccinations now underway, Japan’s service sector is expected to return to growth in H2 2021, aided by a further stimulus package which is aimed to boost the economy through digitalisation and targeting carbon neutrality by 2050.

Japan’s commitment to target carbon neutrality by 2050 is part of the Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) drive which now sits firmly on top of the agenda for governments and corporates alike. In June, Japan’s corporate governance code (CGC) was revised to increase the attention of companies to sustainability as well as ESG more widely. This was identified as an important management issue from the perspective of increasing mid-to long-term corporate value for investors. Alongside this revision to the CGC, there is renewed activism in Japanese markets, with funds and private equity attracted by strong balance sheets – more than half of Japanese companies have net cash versus 10-20% in Western developed markets. Such activism is evident in the recent ousting of Toshiba’s board chairman by shareholders, which marked a watershed moment for corporate governance in Japan.

Unique to Japan is the “keiretsu” model which is a legacy of the economic miracle which followed World War II. One of the characteristics of this model is the now widely criticised practice of “cross-shareholding”, whereby listed Japanese companies have a portfolio of interconnected ownership in each other. Recent figures show almost 11 percent of Japan’s listed companies having a listed shareholder owning a slice of more than 30 percent. This compares with 0.9 percent in the US and 0.2 percent in the UK. Fund managers view such webs as a recipe for complacency, low returns on equity and poor governance. Under pressure from new guidelines from proxy advisers and a shake-up of the Tokyo Stock Exchange (TSE), cross-shareholding is facing an imminent quelling. In January, it was announced that the TSE will streamline in April 2022 by moving to a three-tier system. Inclusion to the TSEs Prime index will depend on reaching a certain level of free-floating market capitalisation as at 31 March 2022, excluding cross-held shares. This requirement should serve to push companies to sell down their cross-held shares.

As corporate governance appears to be making great strides in Japan, we are optimistic that shareholder gains will follow. Indeed, we see opportunities for investing in companies with innovative business models which are actively disrupting traditional Japanese practices. We continue to view international equity exposure, including Japanese equity (and by extension, exposure to the yen) as a critical element in constructing our portfolios, alongside significant market opportunities in the wider Asia Pacific region.

Investment Implications

Economic fundamentals continue to improve and with them, renewed concerns around the future path of interest rates have evolved. These conditions are challenging, with many of the more sensitive sectors of the market likely to outperform as enthusiasm returns. We must try to balance a desire to benefit from these sector rotations with a discipline for long-term fundamental analysis. We work with long-term horizons in mind and will always endeavour to select investments based on their strategic long-term prospects for growth rather than their short-term tactical role within a portfolio. For this reason, we continue to struggle to justify the use of certain asset classes, notably Gold, as part of our portfolio construction. Diversification by asset class and geography remains a core tenet of our strategy. With so much happening at home, we try to give overseas markets due attention. We continue to see attractive opportunities across many markets; the corporate governance moves in Japan being one notable example. Whilst we can take a view on the path for economic fundamentals, including inflation, we can do little to control it, or to control other investors’ response to it. We therefore will attempt to keep our discipline in selecting investments which we believe to be attractive for our clients on a long-term horizon, and to highlight potential short-term volatility as these issues unfold.

As always, our Investment Committee endeavours to be responsible in all investment decisions and seeks only to select investments which are in the best interests of clients. We are committed to the highest standards of research and insist on the same standards where external fund managers are recommended. The processes, policies and procedures of fund managers form a central part of our analysis of external managers and we will continue to assess potential investments across a wide range of quantitative and qualitative

criteria.

Risk warnings

This document has been prepared based on our understanding of current UK law and HM Revenue and Customs practice, both of which may be the subject of change in the future. The opinions expressed herein are those of Cantab Asset Management Ltd and should not be construed as investment advice. Cantab Asset Management Ltd is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. As with all equity-based and bond-based investments, the value and the income therefrom can fall as well as rise and you may not get back all the money that you invested. The value of overseas securities will be influenced by the exchange rate used to convert these to sterling. Investments in stocks and shares should therefore be viewed as a medium to long-term investment. Past performance is not a guide to the future. It is important to note that in selecting ESG investments, a screening out process has taken place which eliminates many investments potentially providing good financial returns. By reducing the universe of possible investments, the investment performance of ESG portfolios might be less than that potentially produced by selecting from the larger unscreened universe.