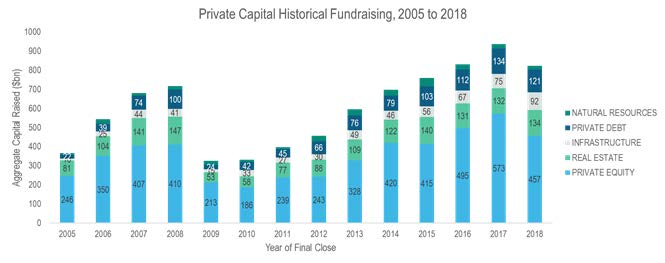

Now that we are in the second decade of this global recovery, it is little surprise that investor flows into the private markets have been on a rising trend. Although this reversed slightly in 2018 (see below), fundraising has been very strong in recent years and, according to Preqin Investor Interviews conducted last November, about one-third of currently-exposed investors intend to increase their private equity exposure in 2019.

With such elevated levels of interest in private equity, we thought it timely to refresh our thinking towards this alternative asset class. As firm believers in liquidity and transparency when dealing with our clients’ portfolios, our natural inclination is to be cautious of any investment that does not meet these criteria – as such, it would be difficult for us to recommend investing in complex limited partnership structures.

Source: Preqin

While we can see no clear way around transparency, we appreciate that very long-term investors may be less worried about liquidity (although as is so often the way, liquidity has its way of deserting you just when you need it the most). However, we question the notion that there is natural alignment between a long-term investor and private equity investment. The typical life cycle of a private equity fund is 10-12 years, from initial capital commitment to the final distributions; but, on average, the majority of the capital is called in years two and three with the largest harvesting coming in years six-to-eight (source: J.P.Morgan) – on a standalone basis, therefore, there is nothing particularly long term in nature as regards private equity.

A commitment to invest consistently across the vintages changes the picture somewhat but, even then, investors must be confident that they will be appropriately compensated for the lack of liquidity and transparency. There is already much evidence to suggest that may not be the case.

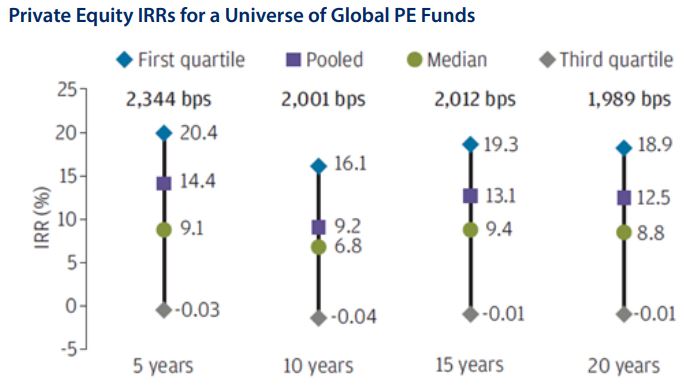

One striking feature of private equity funds is the very wide dispersion of returns generated by the industry. An analysis by Burgiss (see below) showed that, for example, the IRR of the 25th percentile performing fund was 20.4% per annum over the five years to end-2017, while the 75th percentile performing fund generated a negative return. In addition, there is evidence (cf. Kaplan and Schoar, Private Equity Performance) of persistence in the relative performance of private equity general partners – fine if you have access to the very best, in other words, but not so good if you don’t!

Source: Burgiss, J.P.Morgan; data to 31/12/2017

Furthermore, recent years have seen the release of several research reports identifying the similarities of private equity investment returns with those of small-cap indices (or geared plays thereof). There is, of course, a certain intuition to this – private equity investment tends to focus on companies of an equivalent size to those at the lower end of the listed market capitalisation indices and fund their acquisitions with a hefty amount of leverage (6.2x debt/EBITDA in 2018, according to PitchBook). But the point is the liquidity/transparency premium may not be as prevalent as many believe – indeed, one could argue it does not exist at all.

More recently, even vanilla small-cap ETFs have given private equity funds a good run for their money. Using the same timeframes as in the Burgiss analysis, a US S&P 600 small-cap fund generated 10.4% per annum over 10 years versus 6.8% per annum for the median private equity fund as above, and 16.0% per annum versus 9.1% per annum, respectively, over five years (ETF performance data source: iShares). Caveat emptor is a mantra that should probably be ingrained into the psyche of every investor – perhaps for a private equity investor it should be caveat emptor-squared.

Risk warnings

This document has been prepared based on our understanding of current UK law and HM Revenue and Customs practice, both of which may be the subject of change in the future. The opinions expressed herein are those of Cantab Asset Management Ltd and should not be construed as investment advice. Cantab Asset Management Ltd is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. As with all equity-based and bond-based investments, the value and the income therefrom can fall as well as rise and you may not get back all the money that you invested. The value of overseas securities will be influenced by the exchange rate used to convert these to sterling. Investments in stocks and shares should therefore be viewed as a medium to long-term investment. Past performance is not a guide to the future. It is important to note that in selecting ESG investments, a screening out process has taken place which eliminates many investments potentially providing good financial returns. By reducing the universe of possible investments, the investment performance of ESG portfolios might be less than that potentially produced by selecting from the larger unscreened universe.