Many investors want to know where markets are heading. Buying when markets are low and selling when they are high is ideal in theory, but can this be done in practice?

We found it useful to consider some historical perspectives to highlight some of the potential advantages and dangers of trying to time the markets:

“Buy Low and Sell High” or “Buy High and Sell Low”?

Opinion remains divided about the viability of market timing strategies. Independent reviews of different strategies over 30 years generally conclude that their ability to predict the markets is no better than chance, with very few exceptions.1 Outspoken fund manager Terry Smith has said “there are only two types of investors – those who know they can’t make money from market timing, and those who don’t know they can’t”.

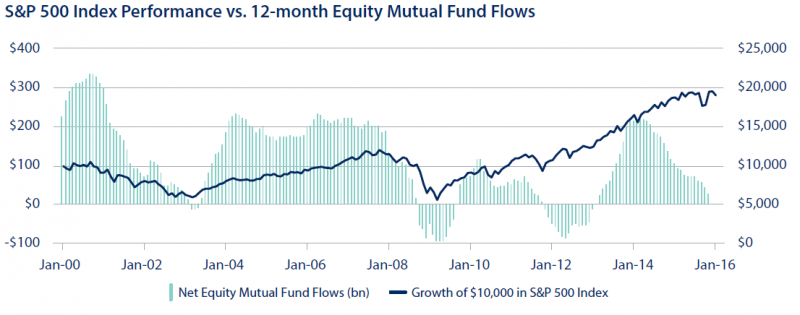

In practice, history suggests that flows of money into and out of the market tend to follow, rather than lead, the level of the markets – investors exhibit a tendency to be overconfident when markets are doing well and panic when markets fall. This is highlighted in the chart below from BlackRock, comparing fund flows in the US with the performance of the S&P500 index:

Sources: BlackRock; Informa Investment Solutions; DB US Equity Strategy; Investment Company Institute (US mutual funds and ETFs). The S&P 500 Index is an unmanaged index that consists of the common stock of 500 large-capitalisation companies, within various industrial sectors, most of which are listed on the New York Stock Exchange. Returns assume reinvestment of dividends. It is not possible to invest directly in an index. The information provided is for illustrative purposes only and is not meant to represent the performance of any particular investment.

Of course, investor demand affects prices, so there ought to be a degree of correlation. Nevertheless, in both 2000/01 and 2007/08, money only started to flow out of funds once the S&P had suffered most of its falls. The chart also highlights the bravery needed to “sell high” in 2007 or “buy low” in December 2008. In the long run, the evidence suggests that timing works against investors, who end up buying high and selling low.

Omitting The Bad Days Or The Good?

Some recent comments have compared the returns for a buy and hold investor with the results of missing the best or worst days of returns. The results appear striking, but the reality is that the best and the worst days roughly cancel each other out, and without the ability to predict which days will be good or bad, these calculations are slightly academic. The chance that you miss a bad day is cancelled out by the risk that you miss a good day.

More importantly, focussing only on the extreme days misses the main driver of returns; compound returns from small but steady gains. If we consider the S&P500 from 1 January 1995 to 31 December 2014, over 71% of daily capital returns in this period fell in the range -1% to +1%. For an investor in the index, the frequency of these “normal” days and the compounding of their returns over time provided the bulk of their return at the end of the twenty years, contributing over 432% in capital growth. Include the compounded dividend yield and the total return rises to over 550%. Once aggregated together, the other 29% of days (those with returns of greater than 1% or less than -1%) make almost no difference to the overall return, contributing a small capital loss of 13%.

Our conclusion is that time in the market is the most important factor in returns for a long term investor. The risk of missing out on compounded growth over time is much more important than potential gains from trying to time the markets.

Distribution of Returns

What happens if we turn our attention closer to home and consider the performance of the FTSE100 in each quarter between 1 January 1986 and 30 September 2015?2

The split between quarterly periods with positive and negative returns is almost exactly 2:1. One might question whether returns were higher in the quarter following a negative period – i.e. is there a recovery bounce after a fall? In fact, the distribution of returns was remarkably similar; the positive/negative split remained at exactly 2:1, and the average quarterly return was only slightly higher (2.39% compared to 2.19%).

So, picking a quarterly period at random, there is twice as much chance of losing out by being out of the market, compared to being invested. This gives further weight to the suggestion that time in the market is most important for an investor with long term objectives.

To Phase or not to Phase?

The theory of phasing is that investing over several tranches at different times helps to smooth returns and reduce risk. Since markets fluctuate, the likelihood is that part of the investment will be made at peaks, and part at troughs, avoiding the risk of investing all at once into a peak, and accepting missing out on the opportunity that everything might be invested at a trough.

If we accept that it is better for long term investors to be fully invested at all times and that we should not try to time the market, why discuss phasing? The answer is that returns should not be viewed in isolation from risk.

This is illustrated by the table below, which compares the returns since 1 January 1986 from investing in the FTSE100 via a lump sum with phasing the investment over three tranches over successive quarters or years3:

| Lump Sum | Quarterly Phasing | Annual Phasing | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average Return | 6.03% | 5.89% | 5.53% |

| Maximum Return | 10.87% | 9.38% | 8.03% |

| Minimum Return | 2.61% | 2.80% | 3.03% |

| Standard Deviation | 1.84% | 1.74% | 1.41% |

On the positive side, phasing an investment over three separate tranches reduces the variation in returns and the dependency of the outcome on the timing of entering the market. On the downside, phasing over successive quarters would have left investors worse off on 2 in 3 occasions. Split the phasing over successive years, and that rises to more than 3 in 4.

Again, the conclusion from history is that time in the market is most important for an investor with long term objectives.

Summary

In theory, successful market timing could add hugely to investment returns. In practice, the available historical evidence suggests that investors have been unable to consistently time the markets and that a long term investor would have been better off remaining fully invested. Whilst the past is no guarantee of the future, and market timing strategies may be able to consistently deliver outperformance in the future, we are yet to see evidence to support this. In addition, trading costs should not be ignored, as they can be a significant detractor for returns. Our conclusion is that investors with long term aims are better off remaining fully invested.

For new investors, historical evidence also suggests that phasing an initial investment over the short term can reduce risk, for a small cost in returns. However, the longer the process is spread out, the longer the investor is out of the market, and the greater the chance of hurting returns.

Disclaimer

This analysis is based on historical returns and is no guarantee of the future.

1e.g. R Bauer and J Dahlquist: “Market Timing and Roulette Wheels”: Financial Analysts Journal vol 57 no 1 (2001) pp 28-40 and “Market Timing and Roulette Wheels Revisited”: Investment Risk and Performance Feature Articles (2012). 2 Data from FE Analytics. 3 Analysis covers periods beginning at each quarter end from 1 January 1986 until 30 September 2010, and assumes investment is held until 30 September 2015 (i.e. a minimum 5 year period). Data taken from FE Analytics.

Risk warnings

This document has been prepared based on our understanding of current UK law and HM Revenue and Customs practice, both of which may be the subject of change in the future. The opinions expressed herein are those of Cantab Asset Management Ltd and should not be construed as investment advice. Cantab Asset Management Ltd is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. As with all equity-based and bond-based investments, the value and the income therefrom can fall as well as rise and you may not get back all the money that you invested. The value of overseas securities will be influenced by the exchange rate used to convert these to sterling. Investments in stocks and shares should therefore be viewed as a medium to long-term investment. Past performance is not a guide to the future. It is important to note that in selecting ESG investments, a screening out process has taken place which eliminates many investments potentially providing good financial returns. By reducing the universe of possible investments, the investment performance of ESG portfolios might be less than that potentially produced by selecting from the larger unscreened universe.